You’re subject to scrutiny and even skepticism as a data-driven marketer.

It doesn’t matter how impressive your results are, or how impeccable your process.

Stakeholders question your numbers. They devalue your analysis. They’re being courted away by “all-flash-no-substance” vendors.

And while it might not seem like it, you may be complicit in the situation.

You’ve convinced yourself that your clients only care about the bottom line and don’t have any patience for “stories.”

The truth is, you just never learned how to use storytelling to elevate your ongoing management and reporting.

That changes now.

Why Use Storytelling in Data-Driven Marketing?

Everyone likes to tell you that storytelling matters. But then to illustrate the importance of stories, they just show you examples of highly-produced commercials and short films.

The problem is, this doesn’t exactly translate to your industry, deliverable format, or client expectations.

After all, we’re dealing with sessions and clicks — not adapting a screenplay for Pixar.

So let’s use a very foundational definition of story from film director Mark W. Travis:

“The telling of an event… in such a way that the listener experiences or learns something just by the fact that he heard the story.”

In other words, a story teaches you or makes you feel something.

Within that framework, these are both stories:

- “You’re fired.”

- “You just won $10,000.”

These statements are missing a three-act structure and overt plot. You’d get banned from telling bedtime stories if this is all you came up with.

But they meet our working definition of “story” for client management purposes.

Can you include traditional literary elements like exposition, conflict, and pacing in your storytelling? Of course.

But you can do a lot of good for your clients, and in turn, your career, just by sticking to the basics outlined here.

Clients Need Story to Recognize Your Value

If a story makes your audience feel something, then the lack of a story means they feel nothing.

At first, that might seem like the goal of working with data.

Cold, hard, emotionless, objective facts. No fluff or bias; just impartial numbers.

But it turns out that emotion, not its absence, actually drives decision and action.

Neuroscientist Antonio Damasio famously treated patients with frontal lobe damage. He discovered that when people were unable to experience emotion, they became “uninvolved spectators in their own lives,” incapable of making decisions.

The article How Emotion Shapes Decision Making summarizes Damasio’s experiences with his patient named Elliott:

Even small decisions were fraught with endless deliberation: making an appointment took 30 minutes, choosing where to eat lunch took all afternoon, even deciding which color pen to use to fill out office forms was a chore. Turns out Elliott’s lack of emotion paralyzed his decision-making.

“Emotion” and “motivation” share the Latin root word “mot,” meaning “move.” They are action words.

Your clients need to feel sufficiently motivated to overcome both inertia and obstacles before they will:

- Implement your recommendations.

- Prioritize content development.

- Approve resource and budget requests.

- Agree to goal adjustments and action plans.

Author and leadership trainer Dr. Paul Homoly put it this way:

“If you’re not telling stories, chances are you’re not connecting with your listeners at the gut level, which makes them less likely to get and commit to your vision. Consequently, your value as an expert is diminished.”

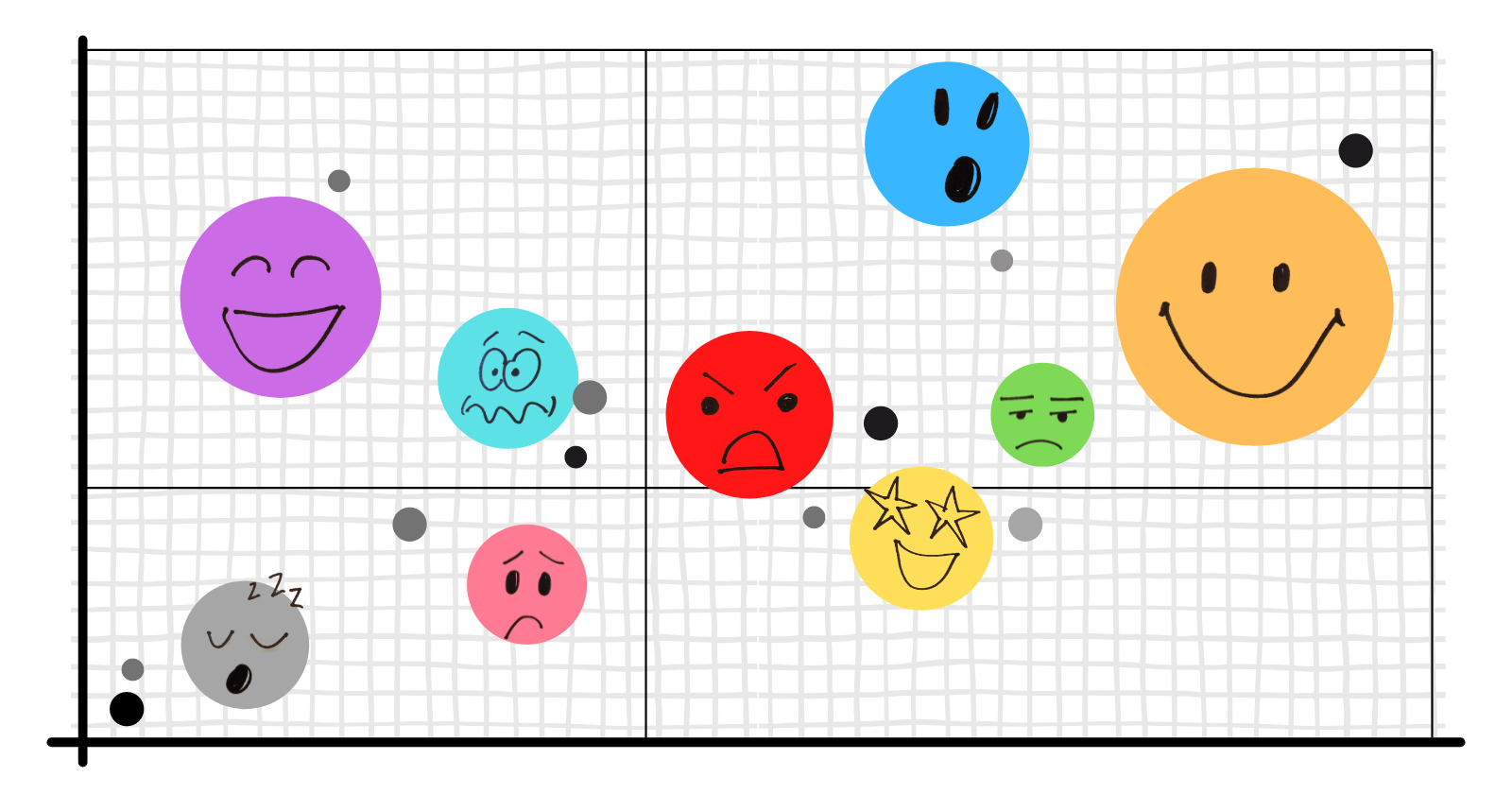

How to Bring Emotion to Client Stories

Before preparing a client email, report, or any deliverable, ask yourself this question:

“How should my client feel in response to this?”

Hopefully not “indifferent” or “confused.” (And no, “informed” is not an emotion.)

But perhaps they’ll feel:

- Upset that a competitor is outspending us.

- Optimistic that we bounced back from a bad month.

- Encouraged that the new strategy is working.

- Worried that we’re slipping in the rankings.

Not every update will result in your client feeling “ecstatic… that we’re with the world’s best agency.”

And that’s okay. In fact, negative emotions can be a powerful way to drive needed action. (More on that later.)

Once you know what your story you’re telling, you can work to tell it even more effectively.

Make Your Audience (Not Your Data Set) Your Story’s Protagonist

A story’s protagonist is “the lens through which your readers see everything.”

In our earlier example, “you’re fired” is a story.

However, “Bob is fired” is not.

That’s because we don’t know Bob.

Maybe he was an embezzler who had it coming.

Maybe he was terrible at his job and created a toxic workplace.

We don’t have the context to feel any particular way over Bob’s firing.

But losing our own job is different. We intrinsically know ourselves, our motives, and how the loss of income will impact our lives. We can quickly tap a deep well of emotion without extra exposition.

Your audience will naturally be using their own experience as the lens through which they view the data you’re presenting, so focus the story on them.

How to Use Protagonists in Your Deliverables

Your protagonist has an external goal (slay the dragon, hit $100 million in revenue), and an internal reason their goal matters to them.

Most of your client deliverables will focus on “what” they want, with the “why” remaining below the surface.

In other words, what they want is to hit their goals, and your story just needs to tell how it’s going for them.

Modify Dashboards to Focus on Your Protagonist’s Goals

If your reporting doesn’t default to highlighting client KPIs (key performance indicators), you’ll need to make some modifications to bring out the story.

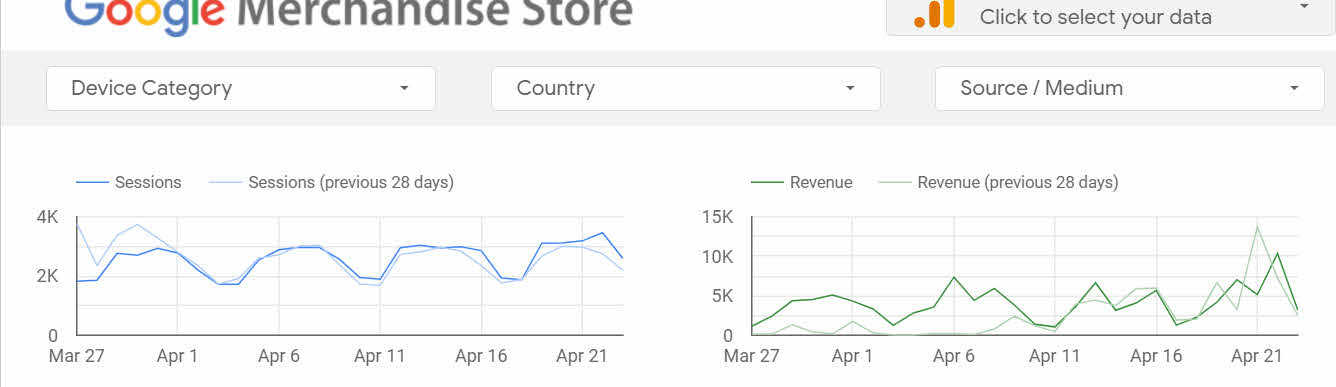

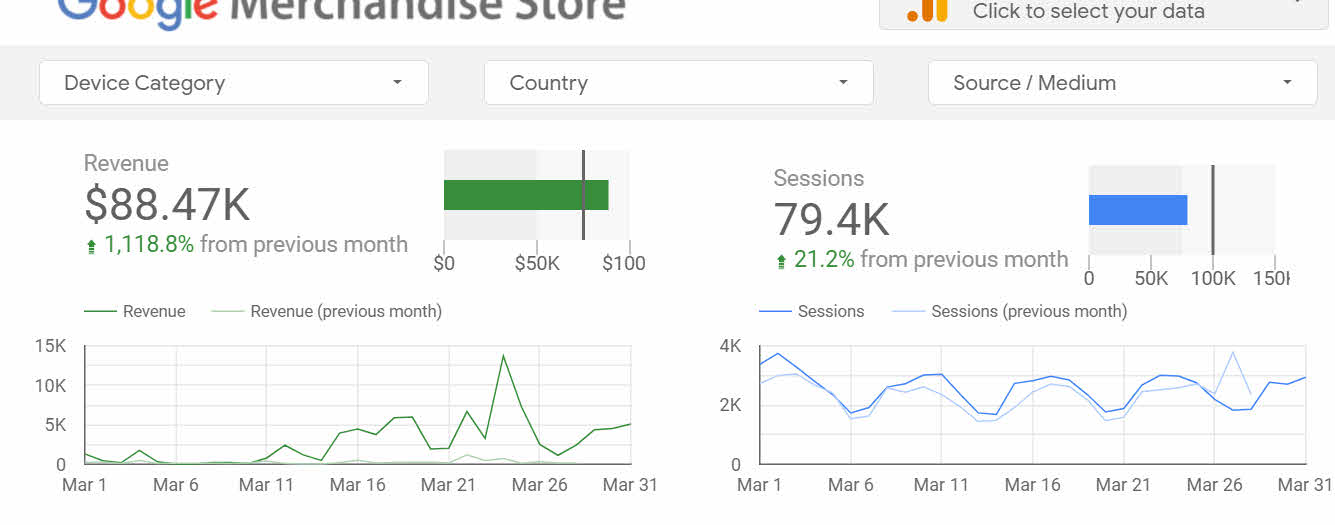

Let’s say your client has a target of driving $75,000 revenue per month.

Your out-of-the-box Google Data Studio reporting template doesn’t tell the story of whether the revenue goal was hit:

Add a revenue scorecard and with a few small adjustments, and you’ve got a KPI-first story that your client can easily interpret:

In this updated report:

- The KPI (revenue) is prominently in the first position with a simple rearrangement of charts.

- Scorecards give “big picture” aggregate performance data.

- Bullet charts show the relationship between the target and actual.

- Fixed month-over-month data answers measurement questions better than rolling comparison charts.

It’s not Shakespeare, but it’s a much better story than randomly ordered charts without any performance summary.

Bonus tip: I like to “celebrate” hitting big milestones with callouts and acknowledgments (gifs, pictures, animations).

It’s an adult equivalent of getting a scratch-n-sniff sticker on a school paper. Even when it’s silly, that extra attention just makes you feel good.

Expose Your Enemies

Most good stories also have an antagonist – an opposing force that causes trouble for the protagonist.

Some common antagonists in data-driven marketing:

- Competitors. These obvious antagonists are easy to villainize and rally against.

- Broken tracking. Wrong or missing data acts as a foil against a true accounting of performance.

- Bad UX. Confusing forms, slow load time, and difficult navigation can keep prospects stuck, which keeps KPIs from being met.

- External trends and forces. Current events that are unrelated to your marketing can still have a huge impact on your marketing.

In your work, you may be tempted to ignore or “edit out” any antagonists.

It’s easy to want to keep things positive, and to protect your clients from worrying about the battles you’re fighting on their behalf.

After all, they hired you so that their stress would go down, not up.

Villains Reveal Heroes

Antagonists can be powerful tools to keep clients engaged and even win buy-in.

When you don’t have an identified enemy, your audience is left to assume the results you’re getting could have happened just as easily without your involvement.

By explaining the challenges you’re facing, you draw your audience in and help them appreciate the dragons you’re slaying for them.

And when they understand the urgency of the problem and how it’s keeping them from their goals, they’re a lot more likely to approve any resources needed to win the battle.

If you’re still not convinced that villains and threats belong in client communications, let’s look at the science behind it.

Because of what’s known as attentional bias, we’re all wired to pay attention to perceived risk — and to generally ignore the status quo.

We also respond to winning and losing differently. Losses are twice as powerful compared to equivalent gains.

When your clients face the threat of a loss if no action is taken against the antagonist, they’re in a highly motivated state to act and, if necessary, change course.

How to Use Antagonists in Your Deliverables

If your client’s goals are not being met, what’s keeping them from getting what they want?

Take the time to identify and name the antagonist. Help your client understand what’s causing the setback, and what resources (if any) are needed to overcome it.

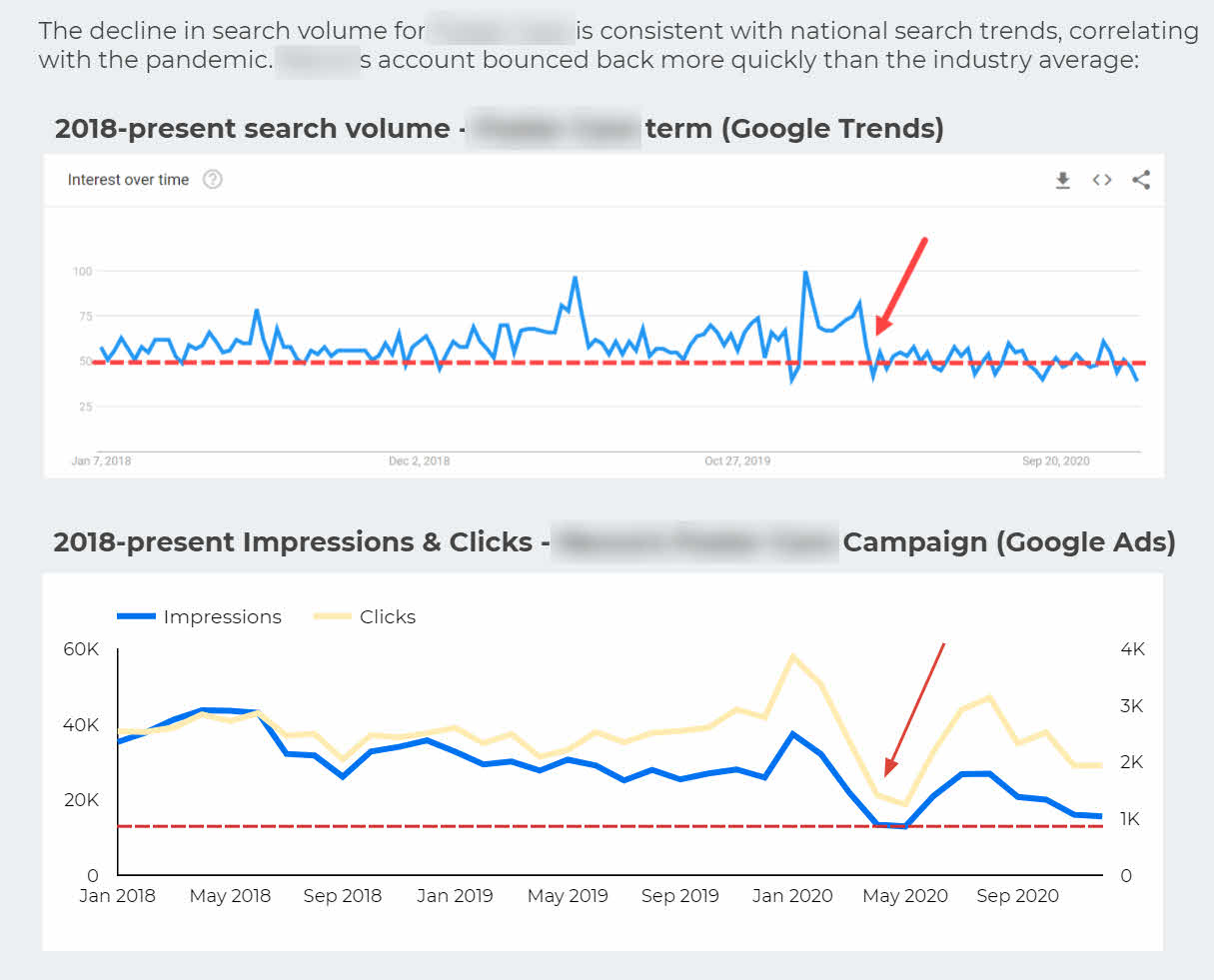

“External Force” Example: Covid-19

The Covid-19 pandemic served as an opposing force to businesses from almost every industry.

Here’s an example of how we told that story for one of our clients:

Even though everyone understands that the pandemic affects businesses, the mechanics of it can still seem murky.

Here, we used a Google Trends chart showing the dip in total search volume. This helped clarify that there weren’t internal or systemic problems with the campaigns.

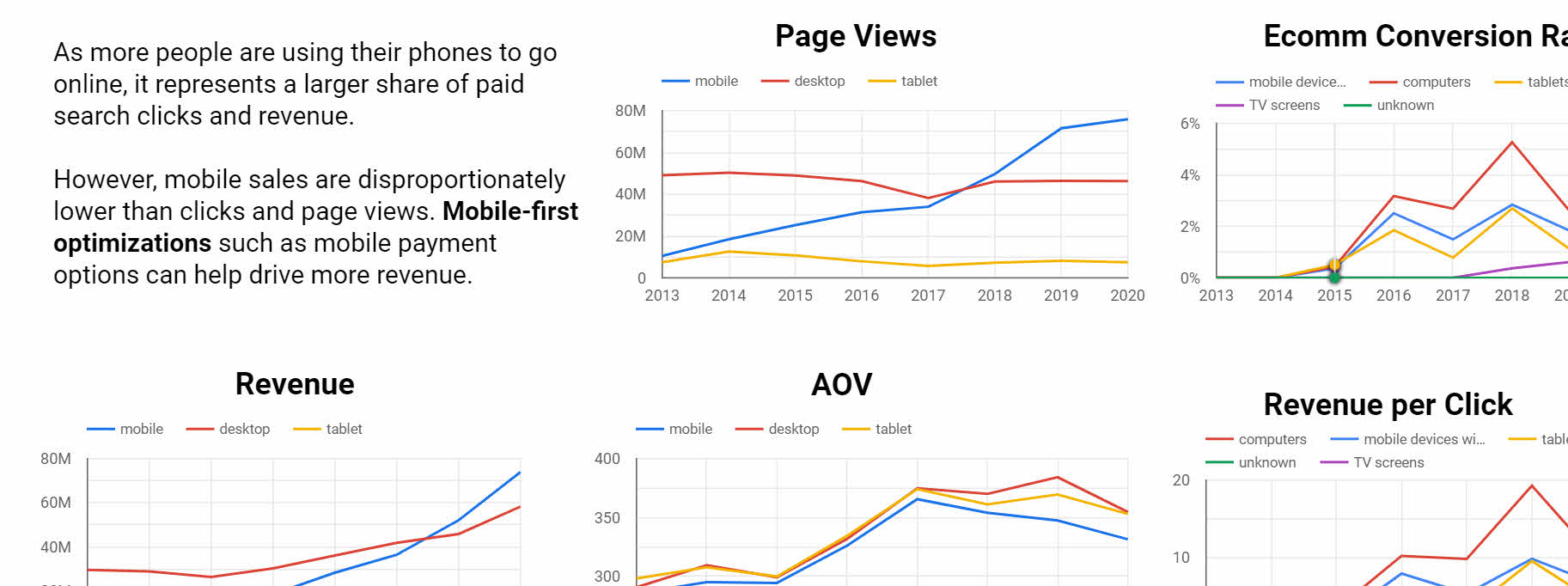

“Internal Force” Example: Bad UX for Mobile

In this example, a client’s own website was keeping them from more revenue. Over time, more of their audience was using mobile to access the site, but the client hadn’t invested in mobile-first optimizations that would make it easier to buy from them.

This report section helped illustrate the hidden cost of inertia, and what it would take to reverse course.

Transparency about antagonists — actual market conditions, threats, and challenges — can drive real improvement. If not examined, nothing changes.

Give Your Audience Context to Understand the Story

A story can only make you feel something if you understand what it’s about.

I could recap a first season episode of This Is Us to my friend May by telling her (spoiler):

“Randall found out Rebecca knew about William.”

She’d know exactly what happened. She’d feel anticipation and tension from just those words.

But my husband James, who doesn’t follow the show, would stare blankly at my recap.

Instead of the single-sentence recap, I might bring him up to speed by saying:

“Randall spent his life trying to discover where he’s from. He just found out that his adoptive mother had known his biological father his entire life, and kept them from meeting.”

The story I’m retelling didn’t change. But when I add the backstory and character relationships, I’ve given James enough context to understand why I’m an emotional wreck.

You can become a better storyteller just by choosing which details to include or omit to match your audience’s experience.

“Quarterly earnings are up 0.5%” could be a champagne-popping story to a global marketing team that’s been working for months to hit that target.

Meanwhile, at a different company, conversions could be up 900%. But the new digital manager doesn’t know what “conversions” means and is embarrassed to ask. He says “Thanks for letting me know,” and changes the subject.

How to Add Context to your Story

Start by asking:

“How can I make this information easier for my audience to understand and interpret?”

You’ll need to know who your audience is to know how much context to add, but it’s hard to overdo it.

Better to define “bounce rate” for someone who already knows, than for someone to read an entire report without grasping what “bounce rate” means.

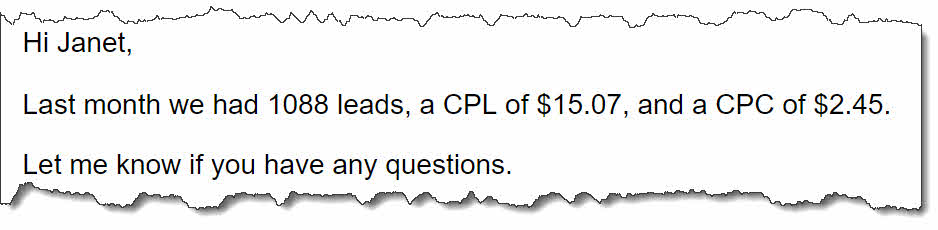

Email Example: Provide Context for Data Points

This email snippet gives the facts of last month’s performance, but Janet has no context for how to interpret or analyze the information:

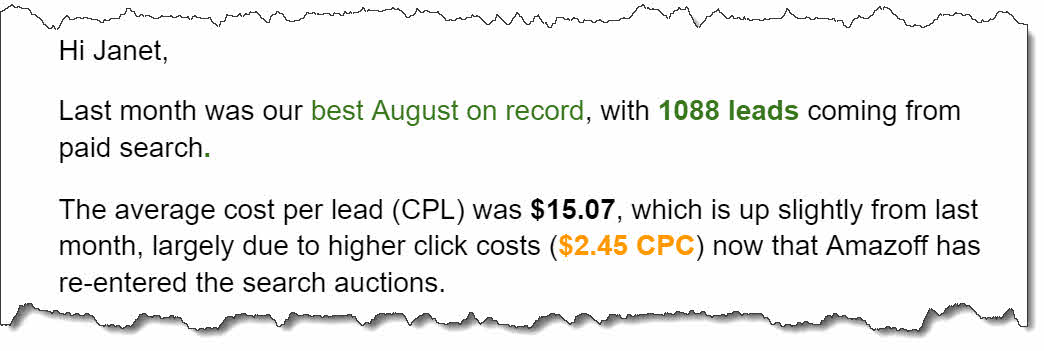

We can make it a better story by adding some visual contrast (color, bolding), spelling out acronyms, and including an explanation about the month’s performance:

Now Janet knows that she can feel good about August leads, but she’ll need to deal with the fact a competitor is driving up advertising costs.

Even More Techniques for Including Context

When it comes to improving your reporting for better comprehension, you’ve got many tools in your toolbox.

Data visualization and information design have become their own disciplines, with many resources for how to present data in a compelling way.

Here are just a few techniques to put into practice:

- Start with the big picture. Use executive summaries and the inverted pyramid. Answer the “5 W’s” (who, what, where, when, why) before drilling into details. Lead with KPIs.

- Use preattentive attributes. Color, form, shape, and size can create patterns and contrast that are quickly processed by the brain for faster comprehension.

- Use microcopy. Provide hints, explanations, and definitions in the small supporting text.

Conclusion

Storytelling may seem like the domain of big brands and animations.

But you can bring story and purpose to your communications with some simple steps:

- Tease out the emotion from the data –How should my client feel in response to this?

- Make your audience the protagonist – Who is my audience and what do they want to achieve?

- Name and expose opposing forces – What’s stopping them from getting what they want?

- Add context – How can I make this easier to understand and interpret?

When you know how to optimize your work for emotion, you get greater comprehension, more buy-in, and a virtuous cycle of better results.

More Resources:

- 3 Critical PPC Tasks You Should Do Every Day

- 9 PPC Mistakes That Impact Success

- PPC 101: A Complete Guide to PPC Marketing Basics

Image Credits

Screenshots and artwork by author, April 2021

![[SEO, PPC & Attribution] Unlocking The Power Of Offline Marketing In A Digital World](https://www.searchenginejournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/sidebar1x-534.png)