Google is doing a much better job of communicating with the search community of late.

Whether it’s the announcement of the latest updates, posting extensive documentation, or answering questions posed directly to a member of the team, Google is generally quick to state what does and doesn’t work in search.

Saying that, I’ve done some digging and there are a number of techniques that Google doesn’t officially support but are still effective – at least to some extent.

As a disclaimer (and to clear my conscience should you decide to implement anything in this post): these tactics aren’t guaranteed to work but have been found to work at least partially.

What Does Google Unofficially Support?

1. Noindex Directives in Robots.Txt File

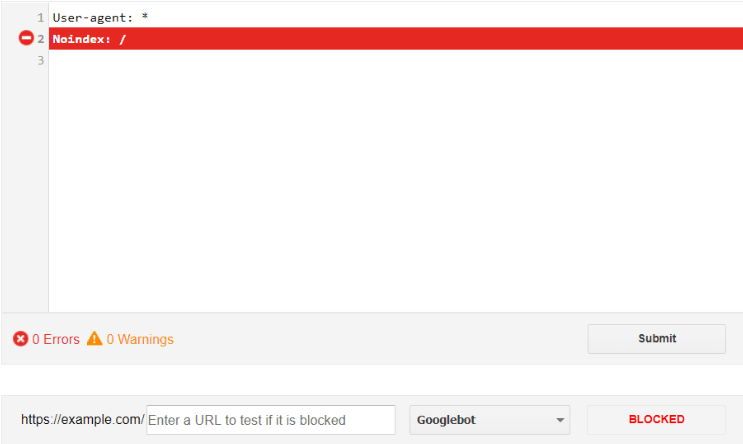

Meta noindex tags applied at the page-level are a tried and trusted staple of keeping pages out of search engine indexes. However, Google also respects most robots directives within a robots.txt file, including noindex.

Officially, Google’s John Mueller has said that noindex robots.txt “shouldn’t be relied on” but our testing at DeepCrawl (disclaimer: I work at DeepCrawl) has shown that this method of noindexing pages still works.

Compared to a meta noindex, robots.txt noindex provides a cleaner, more manageable solution to tell Google that a page shouldn’t be indexed. This method results in less confusion over which directives override which, as robots.txt will override any URL-level directives.

Robots.txt noindex is also preferable to meta noindex because you can noindex groups of URLs by specifying URL patterns rather than applying them on a page-by-page basis.

As with any other robots.txt directive you can test robots.txt noindex using the Robots.txt Tester in Search Console.

2. JS-Injected Canonical Tags

Earlier this year at Google I/O, Tom Greenaway stated that Google only processes the rel=canonical when the page is initially fetched and will be missed if you’re relying on it to be rendered by the client.

If true, this could be problematic for SEO pros making changes through Google Tag Manager, which can sometimes be the best option when faced with long development queues or content management systems that are hard to customize.

Following this, John Mueller later reiterated Greenaway’s point on Twitter:

We (currently) only process the rel=canonical on the initially fetched, non-rendered version.

— John ☆.o(≧▽≦)o.☆ (@JohnMu) May 10, 2018

So that’s that, right?

Well, not quite.

Eoghan Henn and the team at searchViu conducted testing that showed why you shouldn’t take Google’s word as gospel.

After injecting canonicals into several pages via Google Tag Manager, Eoghan found that Google did actually canonicalize to the targets of the JS-injected canonical tags.

With Eoghan’s findings seeming to contradict Google’s recommendation, Mueller responded by conceding that, in light of these tests, that JS-injected canonical tags do work (at least sometimes), but they shouldn’t be relied on.

So, what can we take away from this?

Injecting canonical tags into the rendered version of a page isn’t the ideal scenario, as Eoghan’s tests found that it took three weeks for the JS-injected target URL to be picked up.

However, the more important point here is that we shouldn’t only take Google’s word for things and, as a community, we should be carrying out testing to prove or disprove assumptions, regardless of the source.

3. Hreflang Attributes in Anchor Links

Another instance of Google’s recommendations flying in the face of testing is hreflang attributes in anchor links.

Ordinarily, hreflang links are placed in the head of a page, the response header or in sitemap files, but does Google support these attributes within anchor links?

In a recent Webmaster Hangout, Mueller said that Google neither officially or unofficially supported the use of hreflang in anchor links (e.g., anchor text).

In spite of Mueller’s recommendation, one of our clients’ site has seen that hreflang attributes are actually supported within anchor links, at least partially.

The site in question does not include hreflang links anywhere other than in anchor links and in Google Search Console this client has seen tens of thousands of these picked up as hreflang tags.

While this does seem to go against Google’s recommendations, it is important to note that not all of the hreflang attributes on our client’s site were picked up in Search Console, suggesting that Google only partially supports this method.

We’re currently testing this further to see to what extent Google supports hreflang attributes in anchor links and why some are picked up whereas others aren’t.

Again the important takeaway is not necessarily that you should implement hreflang in this way on your site but that we need to test what we are being told.

4. AJAX Escaped Fragment Solution

For websites with AJAX dynamically-generated content, the escaped fragment solution is a way by which content can be made accessible to search engine bots. This involves using a hashbang (#!) to specify a parameter which allows search engines to rewrite the URL and request content from a static page.

The escaped fragment solution was poorly implemented across the majority of AJAX sites and thankfully, nowadays, solutions like the HTML5 History API allow websites to get the best of both worlds: dynamically-fetched content with clean URLs.

As such, Google has been talking about deprecating the escaped fragment solution for some time and more recently said that it would no longer be supported as of Q2 2018.

We’re now in Q3 and Mueller recently revealed that while Google has largely switched to rendering #! versions rather than the escaped fragment versions, crawling the latter won’t stop immediately because of direct links pointing to them.

So while the AJAX crawling scheme has been officially deprecated, Google hasn’t killed it off just yet.

For the most part, we've switched to rendering pages with #! instead of using the ?_escaped_fragment_= versions (some have direct links too, so crawling them won't immediately stop).

— John ☆.o(≧▽≦)o.☆ (@JohnMu) July 6, 2018

Google’s Ghosts: What They Don’t Support

On the flip side, there is an infinite list of things Google doesn’t support.

I’ve got some examples of things that you might have expected Google to support but actually they don’t. Well, at least not yet.

1. Robots.Txt Crawl Delay Directive

In the early days of the web, it could be helpful to specify a crawl delay in your robots.txt file to indicate how many seconds bots should wait between requesting pages.

Now that most modern servers are able to deal with high volumes of traffic, this directive no longer makes sense and Google ignores it.

However, if you want to alter the rate that Google crawls your site, you can do so in the Site Settings tab within Google Search Console. Google provides a slider that offers a range of crawl rates based on what they judge your site’s server to be able to handle.

Additionally, you can submit special requests to Google by filling out a form that will alert them to problems you’re seeing with how Googlebot is crawling your site.

Conversely, Bing still respects the crawl delay directive and allows you to control crawling by Bingbot by setting a custom crawl pattern within Bing Webmaster Tools.

2. Language Tags

Language tags can be applied to a page in a number of ways (e.g. as a meta tag, as a language attribute in a HTML tag, in a request header).

As a result of the variety and inconsistency in the implementation of language tags across the web, Google ignores them entirely. Instead, Google has opted to have its own system and determine the language of a page by looking at the text itself.

3. Sitemap Priority & Frequency

Sitemap priority and frequency is another case of a crawling initiative gone wrong due to poor implementation by webmasters.

The idea was that you could set a value for each URL which would determine how frequently a URL would be crawled relative to others on the site, with a range from 0.0 to 1.0.

Unfortunately, it was common for webmasters to set the priority for all URLs to the highest priority (1.0) rendering the whole system pointless.

Google has confirmed that they don’t pay attention to any priority values set in sitemaps and instead rely on their own logic to decide how frequently a page should be crawled.

For instance, a recent Webmaster Hangout confirmed that Google will increase crawl rate for pages that change significantly between crawls.

Similarly, the change frequency attribute which was intended to signal to search engines how often a page is updated (daily, weekly, or monthly) is not used by Google to determine crawl rate.

The change frequency attribute doesn’t make sense for the vast majority of pages as they aren’t updated on a daily, weekly, or monthly basis.

4. Cookies

On the whole, Google doesn’t use cookies when crawling pages because it wants to see the page in a stateless way as a new visitor to the site would, and a cookie could change the content served.

The only reason Googlebot will use cookies is on the rare occasion that the content doesn’t work without it.

5. HTTP2

Implementing HTTP/2 can make a real difference to site speed. However, HTTP/2 isn’t yet directly beneficial in the eyes of Google, as Googlebot only crawls with HTTP/1.1, so at this moment in time, it is only beneficial for user experience.

Mueller has said that they may decide to adopt HTTP/2 when crawling because they would be able to cache things differently, however, Google wouldn’t see the same speed effects like a browser would.

What Can We Take Away?

I’m sure there are other examples that I’ve missed, and I’d be interested to hear them if you have any, but this post wasn’t meant to be exhaustive. The main messages I want to drive home are:

- Don’t take Google’s word for it, or anyone else’s for that matter. I’m not suggesting Google is willfully deceptive, but miscommunication is always a possibility considering how many people are involved in maintaining and furthering Google’s search algorithms.

- Techniques that used to work may no longer be relevant. SEO is a constantly evolving space, so we should always be mindful of this.

- Test what you’re told. Or, if that isn’t possible, pose questions and help to disseminate the findings of original research to further our collective understanding.

More SEO Resources:

- When, Where & How to Listen to Google

- Do You Trust Google for SEO Advice?

- Why & How to Track Google Algorithm Updates

Image Credits

All screenshots taken by author, July 2018