Last week, Google began releasing its Pirate update; a penalty against what it called “notorious” piracy sites violating copyright laws.

The first “Pirate” filter rolled out in August 2012. It purportedly caught websites with large numbers of complaints submitted against them for copyright infringements. For two years, copyright advocates cried foul, asserting the penalty — which is similar to better known algorithm updates like Penguin and Panda — was more of a tap than the slap they hoped to see websites publishing pirated media face.

The data analysis I conducted corroborates this claim: the first Pirate filter did nothing significant to penalize torrent websites. I chose torrent sites for scrutiny because, as a group, they have the largest number of complaints filed against them online, as well as in the courts.

Taking a Look at a Boat Load of Torrent Sites

Torrent Freak published a thorough analysis on October 23, 2014 (after I’d begun my research), showing the Pirate update did indeed hit large torrent websites hard, VERY hard. However, the analysis also found that while the larger torrent websites lost rank, small torrent sites often took their place in the SERPs. The update is still rolling out, but the net result might be taking from Peter to give to Paul.

I analyzed search traffic trends of 35 torrent websites from January 2012 to October 2014 using SEMrush data (disclosure: I work for SEMrush, overseeing major accounts). The sample selected for this 2 ¾ years analysis includes sites popular over the time period, as well as those considered most popular now. Data was pulled for domains on a bi-monthly basis during this period.

Metrics reviewed were:

- Estimated Monthly Organic Traffic

- SEMrush Rank

- Cost Per Click on Google Adwords (CPC)

Values shown are based on the top 40 million keywords SEMrush follows and updates constantly.

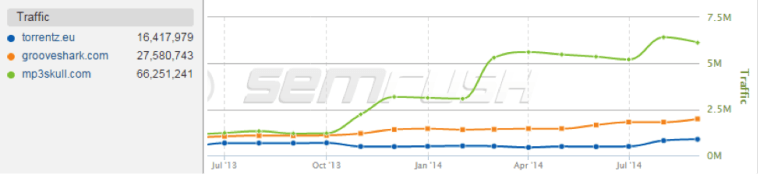

Monthly organic traffic is a function of the aggregate monthly share of traffic a website gets from each keyword based on the SERP position it’s found. Compiling all monthly search traffic, for example, showed mp3skull.com got more traffic from Google in each of the three years of the group. In the first nine months of 2014, it received a whopping 24.6 million visits from the top 40 million keywords tracked, more than any of the other websites during the two-year, nine-month period the penalty was in effect. The visits came from ranking for 1.4 million keywords during the year. On average, it got an estimated 18 visitors from each of these keyword rankings.

SEMrush Rank is based on how much traffic a website gets from ranking in the top 20 organic search results. For example, Wikipedia consistently ranks #1 for the number of monthly visits, but gets less visits from search engines when type-in traffic and referrals are factored to compare websites (factors we want to exclude here).

AdWords CPC helps evaluate how much companies are willing to pay for keywords in Google search. Our data set is for the “free” exposure each keyword has —understanding how much it would cost, on average, at that time to pay for the corresponding AdWords block is telling.

Did Google Let the Pirates Sail Out of Their Safe Harbors?

The Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) has “safe harbor” provisions, which protect companies from possible copyright infringement liability for files uploaded to their websites. Torrent websites and Google’s YouTube follow the same guidelines set forth in the act by responding to take-down requests. Unfortunately, torrent websites are widely understood to stray outside the bounds of the safe harbor designed to help them stay in business. From The Guardian, September 30, 2014:

Grooveshark and its parent company Escape Media Group were liable for copyright infringement by its employees who were directed to upload a total of 5,977 tracks without permission, including songs by Eminem, Green Day, Jay-Z and Madonna.

For all the merits of file-sharing websites, and there are many, this seems flat-out wrong. So wrong, in fact, that in one of the three major lawsuits against the company, their liability totaled $17 billion dollars. OK, perhaps we won’t shed a tear for Madonna, Jay-Z, and those who make as much money as 10,000 middle class folk combined. But, it’s the latters’ livelihood that sparks the most debate.

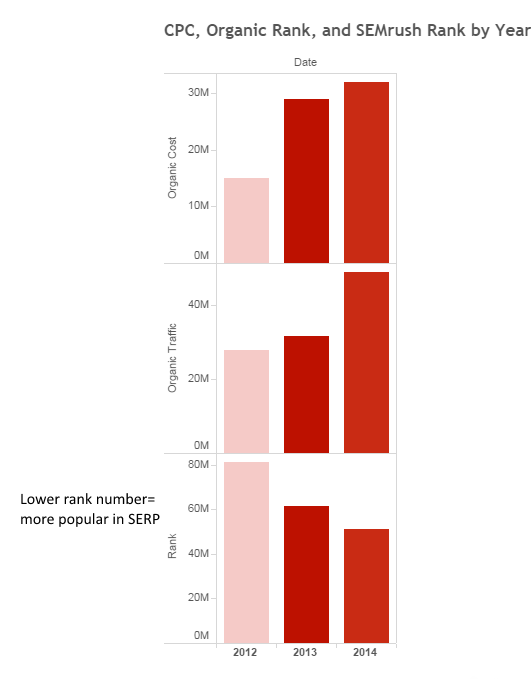

Below is the aggregate change for all 35 torrent sites, bi-monthly, for three measures of success on Google SERPs. Important to note: higher organic traffic numbers are positive for websites, but lower numbers for SEMrush rank are a win. A low number for this rank means the group is moving closer to the top-ranking sites. As you compare these two trends, you would hope to see changes move inversely. This is, in fact, what we see.

Since Pirate rolled out, and especially in 2014, there was a marketed increase in the amount of total organic traffic these websites received from Google. The ranking for these websites relative to all other websites also went up, represented by the graph moving to a lower total number for all the websites’ SEMrush Rank. So the increased traffic was not only due to more people doing searches on the Web for free music, movies, software, etc. — these websites actually gained more traction than other sectors in search on Google.

Perhaps most interesting is the similarity in CPC value for all the ranking words. These two metrics are not commonly compared as highly correlative. That is, we don’t often look for higher traffic from search to show a close corresponding increase in the value of inbound search traffic as judged by what others would pay if they had to buy the traffic in AdWords.

One might think the quality of the traffic would differ considerably. Here we see a striking similarity from the 2012 to 2014 comparisons (2014 is a partial year, but both metrics are representing the partial year). There are many possible explanations for this correlation, but for our purposes what matters is these two measures paint the same picture: torrent websites were by no means pushed down in the value of traffic Google drove or the amount of traffic sent to them after the Pirate filter in 2012.

In compiling this data, the expectation was that sites most successful in 2012 would at least see slower growth with some significant penalty from the August 2012 Pirate filter. Not so.

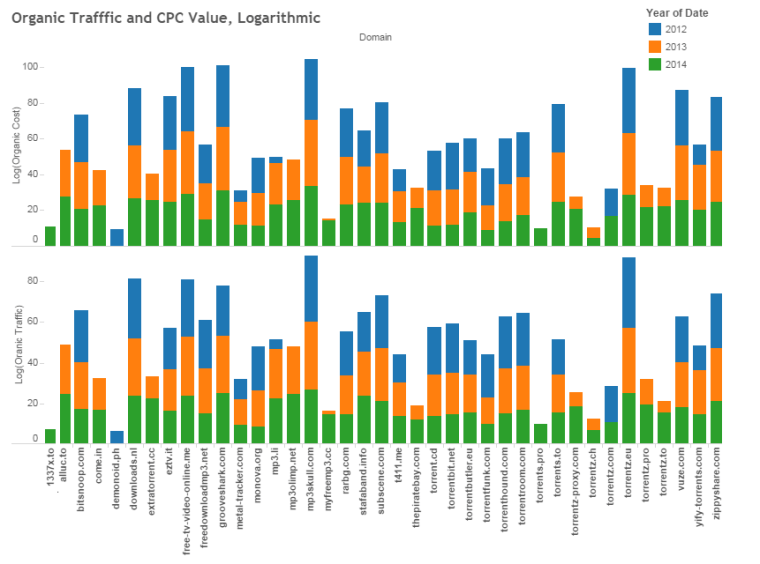

The next graph requires more careful scrutiny, as it’s jam-packed with information (Logarithmic data is used. The differential in search traffic is so great as to render the bottom ¼ performers invisible with raw numbers).

Here you see who the winners and losers were since January 2012. The sample selected for the analysis includes sites popular over this time period, as well as those considered most popular now. Some of the below should probably have been excluded because they show no history prior to 2014 and could skew results. However, there may be just as many websites that were popular and blew up because of legal matters, or changed domains to foreign countries for legal matters.

Below are three of the top five websites in 2012 (you can see the others in the above graph). MP3skull.com helped the entire group with its massive growth. They clearly should have suffered from the 2012 Pirate filter, as they aren’t just a file sharing search site; they host shared files of all sorts on their domain.

The Pirate Bay, one of the most well-known torrent sites of the last 10 years, all but disappeared from the SERPs in 2012. In May of that year, Google announced they had a whopping 6,000 take-down complaints filed under the DMCA. They changed their model to operate as the distributer of BitFile client software — a category purposely left out almost entirely from this analysis of Torrent sites. Google then let them back into their SERPs in 2013 and 2014.

The New York Times didn’t mince words in its August 2012 news analysis of Pirate Bay. Note the use of the word “mole,” as a metaphor no doubt too harsh for those who want less regulation of file sharing, and too generous for those who want tighter control:

Earlier this year, after months of legal wrangling, authorities in a number of countries won an injunction against the Pirate Bay, probably the largest and most famous BitTorrent piracy site on the Web. The order blocked people from entering the site.

In retaliation, the Pirate Bay wrapped up the code that runs its entire Web site, and offered it as a free downloadable file for anyone to copy and install on their own servers.

Thus, whacking one big mole created hundreds of smaller ones.

The Pirate Bay stopped relying on search and said so much in an interview with Torrent Freak just days after the recent update rolled out.

The Changing “Safe Harbor”: Will the Pirate Update Bring the Harbor-Master After YouTube?

Google takes a tough stance against critics of their copyright infringement policing, and they have more at stake than just their search business. If public opinion and copyright laws result in cries for tighter rules on monitoring online copyright piracy, Google also faces new problems with YouTube.

Did Google wait two years to respond to their critics with the Pirate update because more pressure would be applied for lowered rankings for YouTube? Google is widely criticized for giving YouTube videos preferential treatment on the SERPs, as well as preference vis-à-vis content types other than video. The search giant clearly prefers to display YouTube over other popular video sharing websites. Did they drag their feet with an update in part because once they demoted torrent websites, shouts could also be made for more heavy-handed human curation of YouTube videos?

YouTube is second only to Google as a destination for search. It’s also a cash cow, which currently third for the top websites on the web, playing second fiddle to Facebook and Google.com, which sits at #1.

YouTube fits many of the criteria, if not all, for a social network. Anyone who’s worked for a user-generated social network knows one of the largest challenges is having to moderate submitted content using people rather than algorithms. Moderation is expensive. Moderation causes controversy over what is expunged as “infringing”. Moderation begets more moderation when critics proclaim, Look, you really do have the ability to control what is on your website. Yet, algorithmic cleansing of possibly pirated videos is ineffective for sites with less egregious illegal content, like YouTube. This is one of the few topics for which most experts on both sides of the file sharing fence agree.

Please stay tuned for the second and last installment of this analysis, coming to you on SEJ later in November. The piece will look at the changes to these same websites after the update is rolled out for at least a month. As Penguin 3.0 shows us, Google applies updates over a period of weeks now.

Until then, please be sure to drum up some dialogue with your thoughts and ideas here; ideas that always polarize when it comes to file sharing and copyrights.

Image Credits

Featured Image: Lucy Clark via Shutterstock

All images are from Tableau Software and SEMrush

![AI Overviews: We Reverse-Engineered Them So You Don't Have To [+ What You Need To Do Next]](https://www.searchenginejournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/sidebar1x-455.png)